Kissing Spine in Horses (Overriding Spinous Processes)

Updated August 23, 2024 | By: Andris J. Kaneps, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACVSR

What is Kissing Spine in Horses?

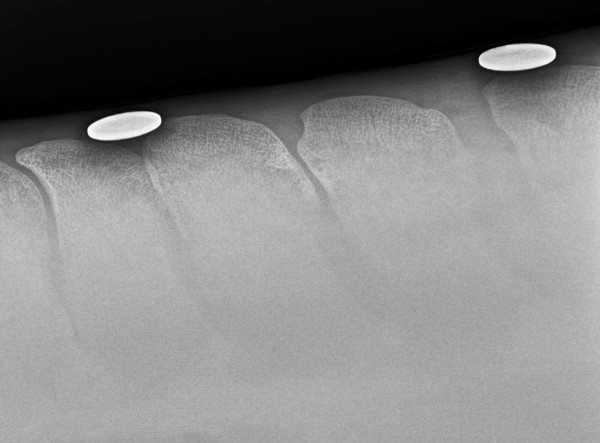

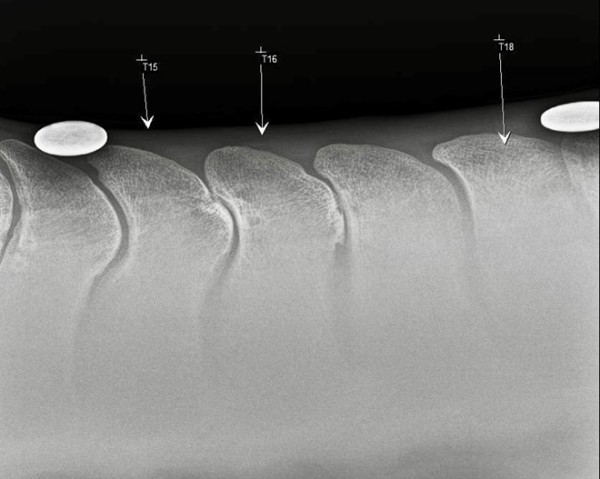

Kissing spine is the most common cause of primary back pain in the horse. Officially known as “overriding dorsal spinous processes” or “spinous process impingement” this term describes the touching or “kissing” of the long, thin bones that project upward from the vertebrae of the spinal column in the horse’s back.

These bony prominences start at the horse’s withers with the first thoracic vertebra (T1) and continue to the point of the hip with the last lumbar vertebra (L6), with T13 – T18 being the most commonly affected. In fact, most kissing spines are seen between T14 - T15 and T15 - T16, where the slant of the spinous processes change direction from a slight angle backward to a slight angle forward. This is also directly underneath where the rider sits. In most horses you can feel the tops of the spines as you touch the groove in the back.

Video on Understanding Kissing Spine

In this Ask the Vet video, Dr. Lydia Gray explains what kissing spine is in horses, how it's treated by veterinarians, and if a horse with the condition can be ridden.

What Breeds of Horses May be Affected by Kissing Spines?

Kissing spines seem more prevalent in thoroughbreds, horses five years of age and under, and dressage horses. The condition also occurs in warmbloods and quarter horses, as well as horses that jump, including hunters, jumpers, and event horses. In some cases, problems develop after a fall or other injury, but more often it is the conformation of the horse (short back) or the vertebrae themselves (narrow interspinal spaces) that is involved.

A team of researchers has identified a genetic component to kissing spines in thoroughbreds, warmbloods, and quarter horses. One group of genes affects whether or not a horse will develop the condition at all, while two other groups of genes affect the severity of the condition. In addition, the researchers noted that a horse’s height has a very strong impact on the chances a horse will develop kissing spines (i.e. taller horses have an increased chance), while sex and age do not appear to be as closely associated as once thought.

How Often are Horses Affected by Kissing Spines?

Many studies have been made to determine the prevalence of kissing spines in horses. On X-ray surveys of horses without back pain, 38-45% of horses were found to have close or overriding dorsal spines [1, 2, 3]. In horses with clinical back pain, an X-ray survey identified 68% to have kissing spines [2]. These studies emphasize that X-ray findings of close or overriding dorsal spines alone does not mean that they are a direct cause of pain or poor performance.

Signs and Symptoms of Kissing Spine in Horses

There are several reasons why a diagnosis of kissing spines in horses can be challenging. First, not every horse with spinous process impingement on X-ray shows acute back pain. Second, there is no one clinical sign that clearly points to kissing spines as the cause. Rather, the horse’s trainer, owner, and veterinarian must work together as a team to identify behavior, performance, and discomfort issues that together tell a story of primary back pain. Third, some indications that a horse may be dealing with kissing spines are subtle and may be interpreted as behavior or training issues.

Some potential signs of kissing spine in horses:

- Shows anxiety on the crossties such as shifting weight, bowel movements, etc.

- Resents grooming, especially over the back area

- Drops or dips the back when the saddle is placed on it

- Acts irritable or bites the air or the crossties when the girth is tightened

- Makes it difficult to mount

- “Scoots” forward as soon as mounted

- Changes from normal temperament, demeanor, and even facial expression while working or being prepared to work

- Has back stiffness or is hollow and inverted

- Demonstrates a resistance to work such as refusing jumps or being “behind the leg”

- Bucks, rears, bolts, kicks out, tosses the head, shies

- Unwilling to go “on the bit” or execute smooth transitions

- Struggles to pick up or maintain the canter, the correct lead, or a proper three-beat gait; cross-canters, has a disunited canter, or breaks from the canter

- Loss of muscle mass across the topline

- Reluctant to roll or lie down

Since many of these signs can be due to a behavioral or training issue - or a medical condition unrelated to the back - it is important to carefully document observations like these and share this detailed history with a veterinarian so that they can come up with the most appropriate diagnostic testing and treatment plan.

Diagnosing Kissing Spines

With a long list of behavioral, performance, and soundness signs possibly pointing to kissing spines in horses, it’s important to confirm the condition or rule it out in order to start appropriate treatment. The diagnosis of any disease or condition starts with the veterinarian taking a complete history, which means sitting down with the owner and trainer and talking through their observations. Signalment – or age, breed, gender – is also critical to forming a diagnosis.

Next, the veterinarian performs a complete physical examination of the horse that includes hands-on palpation of the entire body, including the back. A thorough and systematic lameness exam follows and may include observing the horse while in motion in-hand, on the lunge line, and under saddle, as long as it is safe.

Some veterinarians perform a nerve block (i.e., inject local anesthetic) in the back area and repeat the lameness exam, but this may not be a reliable test for kissing spines. Radiographic images (X-rays) are considered the gold standard for confirming this condition, with nuclear scintigraphy (bone scan), thermography, and ultrasound also contributing valuable information that can be helpful in formulating a treatment plan.

Treatment for Kissing Spines in Horses

Treatment of kissing spines starts with making the horse more comfortable, followed by a program of physical therapy to strengthen back and abdominal muscles, stabilize the posture, and improve mobility. Relieving the pain associated with kissing spines can be approached medically or surgically, and before recommending the best options for a particular case, the veterinarian will consider many factors, such as:

- The severity of the case, as indicated by the clinical signs as well as the X-ray findings

- The availability of certain treatments in the area

- The owner’s budget (time and money)

- The horse’s current and future use

For example, a two-year-old racehorse with five “kissing” spinous processes that can no longer be saddled without pain might be managed differently than a six-year-old dressage horse with subtle performance issues and one narrowed interspinous space.

Medical Therapies

Unless the kissing spines abnormalities are very advanced, most veterinarians will recommend starting with a conservative, medical approach to the treatment of this condition. Methods to control the pain and inflammation and break the muscle spasm cycle and restore motion include:

- injecting corticosteroids directly into the affected interspinal spaces

- therapeutic exercise such as stretching, building topline and core strength, and improving spine mobility

- check saddle fit

- mesotherapy (a pain-dampening technique of injections that stimulate the mesoderm, the middle layer of the skin)

- shock wave therapy

- therapeutic ultrasound

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- muscle relaxants

- chiropractic (veterinary medical manipulation)

- acupuncture

A veterinarian may use one or more of these options depending on the case and his or her record of success with a particular treatment or combination of treatments. Every case is different, and some horses will respond better to one type of therapy than another. If the horse does not improve with medical therapy or the condition recurs quickly, then surgical therapy may be recommended. In a review of medical and surgical treatment for back pain, 42% of horses resolved the pain with medical therapy and 95% resolved with interspinous ligament desmotomy surgery [4].

Kissing Spine Surgery

Veterinarians may recommend surgery for kissing spines as the first treatment option or after an unsuccessful course of medical and physical therapy. Currently, there are two different surgical procedures available. The veterinary “team” made up of the referring vet and the surgeon will recommend the one, or a combination of surgical treatments, that is most suitable for the horse and situation.

Parts of the bony spinous processes themselves are removed, basically shaving off or taking out some of the bone to widen the space. This can be done under general anesthesia or standing sedation and a local nerve block. It is considered the more invasive and costly of the two procedures and requires a recovery and rehabilitation time of 3-6 months

A procedure known as Interspinous Ligament Desmotomy, or ISLD, can be performed while the horse is standing. This involves cutting the ligaments that connect the affected spinous processes. It is generally less invasive, less costly, and some horses return to work in as little as six weeks.

Regardless of which surgical procedure was performed – or whether medical therapy was elected – all horses treated for kissing spine will need physical therapy for long-term improvement.

Rehabilitation and Physical Therapy

The goal of physical therapy or rehabilitation is to safely and slowly get the horse moving in a manner that rebuilds the back and abdominal muscles, expands range of motion, and educates the horse’s body on how to carry itself and a rider correctly. The specific rehab program for an individual horse will depend on the medical or surgical procedures performed, but most begin with a period of hand walking, followed by lunging (usually with a “postural aid device” such as a lunging system). Then, a gradual re-introduction under saddle with an experienced and balanced rider.

Some physical therapy programs incorporate poles or cavaletti. At all stages, it is generally recommended to work the horse in a long and low frame that lifts the back and lowers the neck. It is also critically important to ensure that the saddle fits properly.

Prognosis

While every case is different, the majority of horses with kissing spine that are diagnosed, treated, and rehabbed appropriately are able to return to work. Some will be able to perform at their previous level while others may need a step down in order to remain comfortable. While the formal physical therapy program may have ended, trainers and riders should continue schooling horses in a frame that encourages a rounding of the back, self-carriage, and balance.

Research into kissing spines is ongoing, with one project being the development of models to help identify horses at risk for the condition. This may lead to more appropriate career choices and even early diagnosis and treatment. Owners are urged to strongly consider not breeding horses with kissing spines, now that a genetic component has been identified.

Evidence-Based Resources

- Jeffcott, L B. “Disorders of the thoracolumbar spine of the horse - a survey of 443 cases.” Equine veterinary journal vol. 12,4 (1980): 197-210. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.1980.tb03427.x

- Turner TA. "Overriding spinous processes (“Kissing Spines”) in horses: diagnosis, treatment, and outcome in 212 cases." Proceedings Am Assoc Equine Pract 2011;57:424-430.

- De Graaf K., Enzerink E., van Oijen P., Smeenk A., Dik K. J. "The radiographic frequency of impingement of the dorsal spinous processes at purchase examination and its clinical significance in 220 warmblood sporthorses." Pferdeheilkunde 2015;31, 461-468.

- Coomer, Richard P C et al. “A controlled study evaluating a novel surgical treatment for kissing spines in standing sedated horses.” Veterinary surgery : VS vol. 41,7 (2012): 890-7. doi:10.1111/j.1532-950X.2012.01013.x